from artofmanliness

Sometimes stories are so slender that to become movies, Hollywood has to generously pad and exaggerate the scanty details.

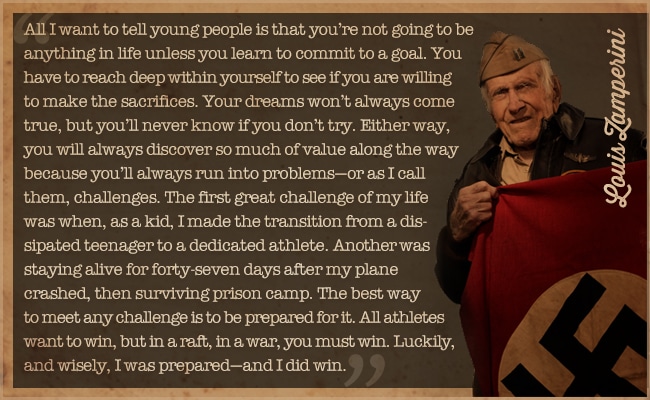

In the case of the current effort to bring the life of Louis Zamperini to the silver screen, the challenge for filmmakers is quite the opposite — managing to fit all the unbelievable details into only 3 hours of running time.

As a boy, Zamperini was a troublemaker who seemed destined to become a bum or a criminal.

At age 15, he found running and turned his life around. He set high school cross-country records, won a scholarship to run track for USC, became a two-time NCAA champion miler, and represented the United States in the 5,000 meters at the 1936 Olympics.

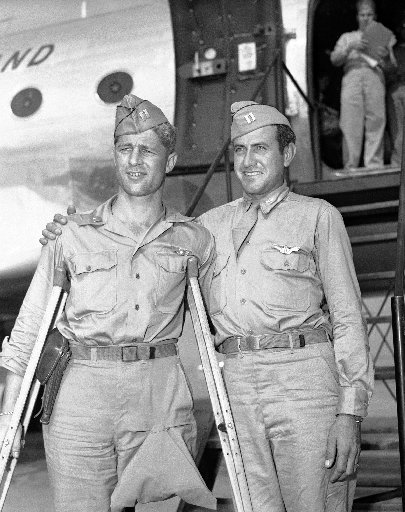

When WWII broke out, Zamperini joined the Army Air Forces, and was deployed to the Pacific as a bombardier on a B-24 Liberator bomber. While flying a rescue mission in search of a downed plane, his bomber crashed into the ocean. 8 of the 11 men aboard were killed.

Louie and two of his crewmates (pilot Russell Allen “Phil” Phillips and Francis “Mac” McNamara) were stranded on a pair of small life rafts. Constantly circled by sharks, with no food and minimal supplies, the men survived for 47 days and drifted 2,000 miles before being rescued/captured by the Japanese.

Being picked up hardly brought an end to Louie’s journey of survival. Having been declared dead stateside, he spent the next two years imprisoned in a series of interrogation and POW camps, where he was starved, diseased, and beaten almost daily by a sadistic guard nicknamed the Bird.

At the end of the war, Louie struggled with alcoholism, anger, and nightmares before finding faith and forgiveness.

Just as it will be impossible for filmmakers to capture the entirety of Louis Zamperini’s amazing life story, I cannot hope to summarize all the incredible lessons that can be learned from it. But here are just a few that will make you a better man.

1. Energy Needs an Outlet

Louis Zamperini was born in Olean, New York, on January 26, 1917. The second of four children, it was clear from the get-go that he would be the hardest for his parents to handle. Even as a toddler he was a bundle of energy that was impossible to corral or constrain.

Young Louie liked action and he liked attention, but the kind he got as a boy wasn’t the variety he hoped for. When the Zamperini family moved to Torrance, California, Louie’s peers mocked his Italian accent, and hit, kicked, and threw stones at him in an effort to get him to curse in his parents’ native language — an outburst which would double them over with laughter. He informed his father of his troubles, who then made Louie a set of weights from lead-filled cans welded to a pipe, set up a punching bag, and taught Louie how to box and fight back. After six months of training, Louis set out to even the score. He pummeled his schoolyard bullies, and won a formidable reputation that deterred future attacks.

Louie’s success emboldened him, and shrunk the already short fuse of his temper. He hit a teacher, threw tomatoes at a police officer, and accosted anyone who crossed him the wrong way. He formed a gang of fellow toughs that engaged in hijinks both comical and criminal; they rung church bells in the middle of the night, grabbed pies from a bakery, and pinched liquor from bootleggers (Louie said they made the best victims, since they couldn’t incriminate themselves by reporting the theft!). Louis loved seeing his escapades written up in the papers.

As a young teenager, Louie only became more surly and wild. He isolated himself from his family and his classmates. But despite his tough façade, inside he felt miserable. He wanted to be better and not cause his parents so many headaches and heartaches, but he continued to feel like “the proverbial square peg who couldn’t fit into the round hole…or appreciate what he had.”

Luckily, Louie’s older brother Pete had a plan. Pete had seen how quickly Louie could run away from the scenes of his crimes, and figured that speed could be put to better use. He understood that Louie craved recognition, and decided to help him get it in a more constructive way. To that end, he pushed his brother into joining the high school track team. At first Louie balked, and his first race was a disaster; he came in dead last. But Pete incessantly dogged him to enter another meet, and this time the results improved; Louie placed third, and more importantly, experienced a taste of the thrill of competition and the sweet sound of his name being shouted by a crowd of spectators.

At first Louie still fought against wholly giving himself over to becoming an athlete. His training regimen was spotty and he continued to drink and smoke. But after a short and unromantic stint as a train-hopping hobo, and the realization that he didn’t want to spend his adult life as a bum, he was ready to tell Pete: “You win. I’m going all out to be a runner.” As Louie later recalled, “It was the first wise decision of my life.”

As the fledging runner trained, improved, and started to win, his neighbors and classmates started to treat him much differently. He began to catch “a whiff of respect: Louis Zamperini, the wop hoodlum from nowhere, had made a success of himself.”

Louie would always have a temper, and a penchant for rebellion, but here began his training in how to harness it for worthy ends. He kept his fire and fight, but made them his servant instead of his master. It was a power that would serve him well in the many challenges to come.

2. Toughness Is the Ultimate Preparation for Any Exigency

The transformation from local hellraiser to dedicated athlete wasn’t easy. As Louie later recalled, “I still wanted to do almost everything my way.” On his training runs, Pete would follow behind his whining brother on a bike, hitting him with a stick to prod him along. Louie gradually began “to accept the physical pain of training” and Pete had to employ the switch less and less often. He gave up smoking and drinking and even ice cream sundaes, and he did it because he didn’t want to let his brother down. But Pete understood that Louie needed to want it for himself. “You’ve got to develop self-discipline,” Pete told his brother. “I can’t always be around.” Louie took the advice to heart and worked to develop his own commitment to running:

“I knew however much I struggled against it, that running was the right course to follow. To stay on the straight and narrow I made a secret pact with myself to train every day for a year, no matter what the weather. If I missed working out at school, or the track was muddy, I’d put on my running shoes at night and trot around my block five or six times, about a mile and a half. That winter we had two sandstorms and I had to tie a wet handkerchief across my face and mouth just to go out. I also kept boxing, to develop my chest muscles. In the end I was probably even more disciplined than Pete wanted me to be.”

As part of Louie’s self-created training regimen, he started to literally run everywhere. Instead of hitchhiking to the beach as he once had, he would run the four miles there, run 2 more miles along the beach, and then run the 4 miles back home. When his mother asked him to run to the store to pick up something for her, that’s exactly what he did. On weekends, he’d “head for the mountains and run around lakes, chase deer, jump over rattlesnakes and fallen trees and streams.”

Louie also strengthened his lungs by practicing how long he could hold his breath at the bottom of the local pool. He’d sit holding on to the drain grate until his friends feared he would drown and would jump in to save him. And he researched the workouts of his fellow runners, and then doubled them for himself. “When I started to beat them,” Louie later remembered, “I knew the simple secret: hard work.”

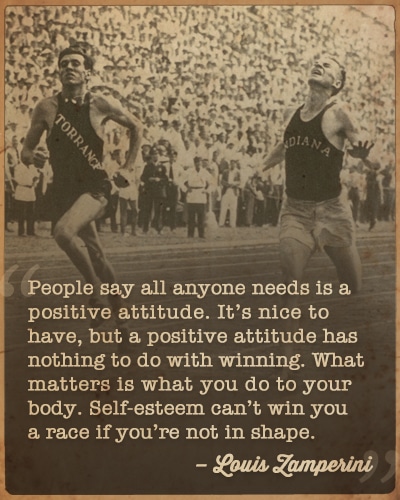

Louie continued to challenge his body and

strengthen his willpower when he became a collegiate runner. His coach at USC forbid his athletes from running uphill, including stairs, believing it was bad for the heart. But Louie had spent plenty of time scaling hills on his solo runs, and knew how good it was for his body and his ability to embrace pain. So he did his own

stair workouts outside official practice:

“Every evening I’d climb the Coliseum fence and do the ‘agony run.’ At the top my legs seared with fire, then I’d walk across a row, go down again, and up another staircase. I did that after each normal workout. Here’s why. People say all anyone needs is a positive attitude. It’s nice to have, but a positive attitude has nothing to do with winning. I often had a defeatist attitude before a race. What matters is what you do to your body. Self-esteem can’t win you a race if you’re not in shape.”

Louie’s studied cultivation of toughness put him in good stead for his mile-long races. He was famous for his ability to

dig deep and dial up a ferocious kick on the last lap. At the start of his running career, he had often complained to Pete about the pain and exhaustion inherent in that final, minute-long push to the finish line. His brother had then given him a piece of advice that always stuck with Louie: “Isn’t one minute of pain worth a lifetime of glory?”

That was the question running through Louie’s mind during the final for the 5,000 meters at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. He fell behind the lead runners and stayed there for most of the race. But as he moved into the last lap, he remembered Pete’s advice: “When I felt done-in was the time to exert myself.” Louie kicked it into high gear, and turned in a scorching lap time of 56 seconds, enough for 8th place and to become the first American to hit the tape. His last lap was so memorable, even the Führer himself asked to meet with him after the race to shake Louie’s hand.

Louie demonstrated his toughness in a different way during a NCAA meet in 1938. A group of runners had conspired to sabotage him by roughing him up mid-race. As the competitors raced around the track and jostled for position, the runners blocked Louie in, and the one directly in front of him reached back with his foot and raked his shoes’ razor-sharp spikes across Louie’s shin, creating three gashes a quarter-inch deep and an inch and a half long. When the aggressor did it a second time, the wounds widened and blood began to run down Louie’s leg. He tried to escape the box, but the runner on his flanks threw an elbow into his ribs, causing a hairline fracture. Even with the wind knocked out of him, and his socks filling with blood, Louie remained undaunted. He finally managed to sprint free and cross the finish line ahead of the pack. His would-be saboteurs’ plans had been foiled; not only had Louie won, but he had broken the national collegiate record.

All of these episodes of

toughness trained and toughness won might have been just a footnote in yet another athlete’s story, except for how they singularly prepared him for a much more trying contest to come: Louie vs. Death.

When Zamperini emerged from the wreckage of his bomber and pulled himself into a life raft in the middle of the ocean, it was his confidence in his body, his self-discipline, and his ability to withstand pain in the pursuit of a goal that enabled him to maintain his composure. He remembers his initial thoughts as he assessed the dire situation:

“Look, no one wants to crash, but we had. I knew the way to handle it was to take a deep breath, relax, and keep a cool head. Survival was a challenge, and the way to meet it was to be prepared. I’d trained myself to make it. I was in top physical condition.”

The response of Mac, one of Louie’s two raft mates, could not have been more different; he started wailing about how they were all going to die. While a slap across the face from Louie snapped him out of it, Mac’s panic continued to grow within. When Louie woke up the first morning after the crash, he found all the chocolate bars – the men’s only form of subsistence – had been gobbled up by Mac while he and Phil had been sleeping. The unthinkingly selfish act was a harbinger of what was to come – Louie and Phil would remain calm, hopeful, and mentally strong, while Mac would slip into an anxious, paralyzing malaise.

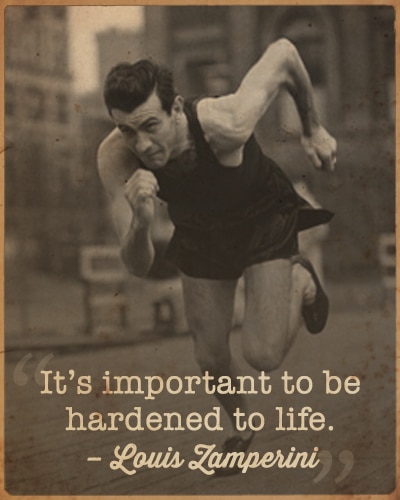

What accounts for the difference in the men’s responses to the same crisis? In

Unbroken, the bestselling account of Louie’s life, author Laura Hillenbrand calls it a “mystery” and muses that perhaps genetics played a factor. Some people are surely born more optimistic than others, but Louie had his own, more frank theory on the matter:

“Mac never took proper care of himself. On the base he skipped our physical-fitness program. He chain-smoked. Drank. Spent his nights in Honolulu doing who knew what. He also missed meals. We had pretty good food in the dining room, but he’d come in, eat whatever was sweet, and leave. You couldn’t make him listen. Several cups of coffee and three pieces of pie? No problem. Mac had developed a sweet tooth long before he met our chocolate. I should have known I couldn’t trust him…

Everybody in the service gets the same combat training. We go to the front line with the same equipment. When the chips are down, some will panic and run and get court-martialed. Why? Because we’re not all brought up the same. I was raised to face any challenge. If a guy’s raised with short pants and pampering, sure, he goes through the same training, but in combat he can’t face it. He hasn’t been hardened to life.

It’s important to be hardened to life.

Today kids cut their teeth on video games. I’d rather play real games. This generation may be ready to handle robotic equipment and fly planes with computers, but are they ready to withstand the inevitable counterattack? Are they emotionally stable? Are they callous enough to accept hardship? Can they face defeat without falling apart?”

In the initial aftermath of the crash as Louie bandaged Phil’s head wound, he said softly, “Boy, Zamp, I’m glad it was you.” When the chips are down, isn’t that something every man would like to hear?

3. Always Have a Purpose and a Vision for the Future

Another big difference between how Louie and Mac approached their dilemma was that Zamperini focused on the future, and on keeping himself busy with tasks, even small ones, that helped get him closer to it. Though he himself experienced a moment of anxiety as he surveyed how few supplies they had at their disposal, “rather than give in, I made myself a promise: no matter what lay ahead, I’d never think about dying, only about living… I adapted myself to my fate instead of resisting it. Rescue would be nice, but survival was most important.” If in his youth, Louie’s fight and resourcefulness had gotten him into trouble, now they were his ace in the hole for beating back death and coming out of the crucible alive.

Louie inventoried what they’d need to survive: “food, water, and a sharp mind.” As to the first two requirements, he set to work testing out various fishing methods with their limited equipment, catching birds that landed on the raft, and turning canvas cases into rain catching devices. He was a shipwrecked MacGyver and his persistent ingenuity was so inspiring,

we’ve dedicated a separate post to detailing it. The small successes he had with his experiments fueled his confidence; it became a positive cycle, in which the more he and Phil tried to survive, the more hopeful they became about their chances, and the more strength they developed to stick it out. In contrast, Mac remained passive, and this became a cycle as well; the more he withdrew, the more listless and dejected he became.

Beyond the procurement of food and water, Louie made mental exercise a top priority. He had read the story of what had happened to another pilot and his men who were adrift at sea for 34 days. After several weeks, many of those castaways had gone to pieces, seeing hallucinations and babbling to themselves. As Hillenbrand writes, this knowledge made Louie “determined that no matter what happened to their bodies, their minds would stay under their control.”

Louie thought back to a college class he had taken in which the professor compared the mind to a muscle that would atrophy through disuse. So he decided that he and his fellow castaways would give their brains daily workouts. The raft became a “nonstop quiz show” with Louie and Phil constantly trading questions back and forth. They talked about their families, the dates they’d been on, their college days, and what they wanted to do

when (never

if) they got home. Each response would bring a follow-up question from the other (

no conversational narcissism here!). Louie would describe his mother’s delicious Italian dishes in detail, and the phantom meals would temporarily fill the men’s bellies. As Hillenbrand writes, “For Louie and Phil, the conversations were healing, pulling them out of their suffering and setting the future before them as a concrete thing. As they imagined themselves back in the world again, they willed a happy ending onto their ordeal and made it their expectation. With these talks, they created something to live for.”

Mac, on the other hand, rarely participated in the discussions, and slipped further away. As Louie put it, he “lost his vision of the future.” On the 33rd day of their odyssey, though he had gotten as much food and water as his raftmates, Mac passed away.

Louie carried his field-tested conviction in the importance of active purpose throughout the rest of his brutal journey towards home. When the Japanese rescued/captured Louie from his raft, they first placed him in a tiny, sweltering, maggot-filled cell on the island of Kwajalein. Here guards regularly kicked and punched him for fun, and poked sticks through the bars of his cage, treating him like zoo animal. To take his mind off his de-humanizing circumstances, Louie spent his time memorizing the names of the 9 Marines that had been inscribed on the wall of his pen — men who had once shared his cell before being executed. If he was freed, he wanted to be able to pass along the list to Allied intelligence. “It was my small way of keeping hope alive,” Louie said.

When he was later transferred to a series of interrogation and POW camps, Louie put his energy into fueling an information network between the prisoners. He kept a tiny diary made of rice paste, even though he knew its discovery would bring a severe beating, and he daringly stole newspapers from guards when they weren’t looking. News of Allied progress was crucial in buoying the spirits of the men. He also took part in the camp’s well-organized ring of thievery – stealing food, supplies, and tobacco to distribute to the prisoners.

Even in darkest moments of camp life, when he was beaten daily and lay sick in his bunk with dysentery and scorching fevers, Louie held to the prospect of being rescued and refused to give up. In his mind he envisioned embracing his family again, competing in another Olympics, living his life.

When his camp was finally liberated, and he found himself aboard a train on the first leg of his long journey home, some of the men around him “grumbled about years of miserable treatment or complained that we should have been liberated from Camp 4-B sooner.” But Louie didn’t join in and continued to uphold the philosophy that had gotten him through those brutal, de-humanizing years: “I’d made up my mind to stay focused on the future, not the past.”

4. A Man Keeps His Promises

When Louie was captured by the Japanese, and imprisoned on Kwajalein, he wondered why he wasn’t executed like the other Marines who had once shared his cell. As his internment progressed, he found out.

One day, he was taken from his prison camp to a radio station that broadcast Japanese propaganda programs. His hosts treated him kindly and showed him around the premises. There was a cafeteria with hot, heaping portions of American-style food, and clean hotel-style beds with sheets and pillows. Louie could stay here, the men told him, and never have to return to camp, never have to see the Bird again, if he would simply do a little broadcast for them. The message they wanted him to read wasn’t overtly traitorous, it just expressed his astonishment that the US government had declared him dead, and hurt his family with the news, when he really was alive and well. But as Hillenbrand explains, Louie knew its purpose was to “embarrass America and undermine American soldiers’ faith in the government.” He realized he had been kept alive because his prominence as an Olympic runner would make him a more effective propaganda tool. And he understood that once he read one message for them, they’d ask him to read increasingly critical ones, and there would be no way out. Though refusal meant returning to a wooden slab infested with bed bugs, starvation rations, and the endless beatings of a mad man, Louie declined the offer. The Japanese broadcasters pressed, warned he’d be punished, and still he refused. Acceptance was not even an option for Louie: “I’d taken an oath as an officer.”

Living up to another promise would prove more difficult. While floating on their life raft, Louie and his crewmates once went 6 days without water. The men felt on the doorstep of death, and Louie prayed fervently to God, pledging that he would dedicate his life to him if only it would rain. The next day brought a downpour. Two more times they prayed, and two more times the rains came. Throughout his later captivity, Louie would repeat his promise, praying, “Lord, bring me back safely from the war and I’ll seek you and serve you.”

When Louie was finally freed from his torments and sent back home, his vow was forgotten amongst numerous homecoming parties and let-it-all-hang-out celebrations. “Ignoring the future and the past,” he would later remember, “I drank and danced and gorged myself, and forgot to thank anyone, including God, for my being alive…I completely dismissed my promises because no one could remind me of them except myself.”

While the revelry took his mind off his harrowing experiences for a time, inside the scars and trauma of war festered. Louie’s fun-loving drinking turned into alcoholism, he struggled to find steady employment, and he was terrorized in his dreams by the Bird. His post-war marriage disintegrated, and his wife wanted a divorce. Bereft of the kind of active purpose that had once carried him through his most trying of challenges, he centered all his energy on a fantasy of revenge – on finding the Bird and killing him.

In a last ditch effort to save their marriage, his wife begged Louie to come with her to a Billy Graham revival meeting. Louie balked; he had no need for religion in his life. She persisted, and Louie reluctantly tagged along. Graham’s preaching made him feel condemned, angry, and defensive; he bolted home halfway through.

His wife managed to convince him to attend another meeting, and though he again felt like running away, this time the memory he had tried so long to forget burst upon his mind: he saw himself in the life raft, parched, desperate, dying, the heavens opening, and the cool rain drops falling on his skin. Louie fell to his knees and asked God “to forgive me for not having kept the promises I’d made during the war, and for my sinful life. I made no excuses.” After the meeting, Louie felt filled with forgiveness not only for himself, but for his former captors and tormentors. He poured all of his alcohol into the sink, and experienced a joyful, “enveloping calm.” The Bird never again came to him in his dreams. And he spent the rest of his life doing exactly what he had promised – offering inspiration to those adrift in their own ocean of struggles.

_____________

Sources: